June 2023 Case Study

by Adrianna Gonzalez, MD

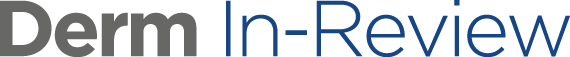

A 29-year-old male with no significant past medical history presented with complaints of a generalized rash which began two months prior. He stated the eruption began as a few lesions in the trunk that progressively grew in number and generalized to involve upper and lower extremities, buttocks, and genitals. He stated rash was associated with significant itch. Of note, he stated he had taken a new medication several weeks prior to the onset of his rash. Findings on clinical examination can be seen in Figure 1. A 4mm punch biopsy of a lesion on his mid back was performed. Histopathological examination revealed orthokeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis with sawtoothing rete ridge pattern, dyskeratotic keratinocytes and a band-like lymphocytic infiltrate.

Which of the following statements is false regarding this patient’s condition?

A.) The oral mucosa is the most commonly involved body site in this entity

B.) On histology, dyskeratotic keratinocytes are classically found at the upper level of the epidermis

C.) Direct immunofluorescence may be positive for “shaggy” fibrinogen deposits along the dermoepidermal junction

D.) Flares may be triggered by certain contact allergens including copper

E.) The majority of cases will remit within 2 years

Correct Answer: B.) On histology, dyskeratotic keratinocytes are classically found at the upper level of the epidermis

The statement in answer choice B is FALSE, which makes this the correct answer. The clinical and histopathological findings in this case are consistent with lichen planus (LP). On histology, LP is characterized by compact orthokeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, sawtooth pattern of rete ridges, vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer, dyskeratotic keratinocytes (Civatte bodies), and a band-like lymphocytic infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ). Dyskeratotic keratinocytes are classically present at the lower levels of the epidermis and at the superficial papillary dermis near the basal layer, the site of destruction.1 Dyskeratotic keratinocytes can be seen in the suprabasilar, upper epidermal layer in erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis.2 Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) demonstrates “shaggy” deposition of fibrinogen along the basement membrane zone, as well as staining of colloid bodies with one or more of IgM, IgG, IgA and C3 (answer C).

Lichen planus is an inflammatory disorder of the skin, mucosa, hair and nails. Although the incidence appears to vary throughout geographical areas, the oral mucosa has been found to be the most commonly involved body site in most study populations (answer A).1,3 Oral lesions can be observed in over 50% of patients with LP, and can often be the only site of involvement.2 A recent epidemiological study estimated that the global pooled prevalence of oral LP was 0.89% among the general population and 0.98% among clinical patients.4 Cutaneous LP is thought to affect < 1% of the population worldwide and commonly presents as pruritic, purple, polygonal, flat-topped papules commonly involving the extremities and lower back.5 There are numerous variants of cutaneous LP, including actinic, annular, atrophic, bullous, drug-induced, genital, hypertrophic, inverse, linear, LP pigmentosus and lichen planopilaris. LP may also involve the nails and present with longitudinal ridging, trachyonychia, thinning, dorsal pterygium and even 20 nail dystrophy. While its pathophysiology has not been fully elucidated, LP is thought to be caused by an altered cellular immune response, in which cytotoxic CD8+ T cells attack basal keratinocytes. LP has been associated with various triggers, including infections such as hepatitis C virus (more common in oral erosive LP), medications, contact allergens, vaccinations (hepatitis B virus and influenza) and genetics. Implicated contact allergens include gold, mercury amalgam and copper (answer D).1 Most cases of LP self-resolve within 1-2 years (answer E). Oral LP (especially oral erosive LP), nail LP and hypertrophic LP tend to be persistent and recalcitrant to treatment.

References

- Boch K, Langan EA, Kridin K, Zillikens D, Ludwig RJ, Bieber K. Lichen Planus. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:737813.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo, J. L., & Schaffer, J. Dermatology. Fourth Edition ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen Planus. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL)2022.

- Li C, Tang X, Zheng X, et al. Global Prevalence and Incidence Estimates of Oral Lichen Planus: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(2):172-181.

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: Clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(5):789-804.